By providing your information, you agree to our Terms of Use and our Privacy Policy. We use vendors that may also process your information to help provide our services.

ektor garcia’s work traverses the psychological and the political, quietly contending with the ways in which power structures invade the most intimate spaces of the self. Incorporating ancient craft techniques, found artifacts of personal significance, and allusions to Mesoamerican myths, his sculptures and installations might appear to retreat into the past or emerge from a solipsistic inner world. But through gestures that summon ancestral memory and systems of belief, he materializes a search for belonging in the present and in the liminal spaces between different cultural identities. Even centuries after the first points of contact, colonial forces and hegemonic frameworks of thought continue to inscribe lived reality, and garcia’s practice probes the internalization of this violence. In his hands—wielding needles that can pierce or mend with care and turn bound fibers into diaphanous woven cloth—personal narratives of survival and healing never resolve, but instead transform implements of pain and repair into sources of pleasure and the means by which to conceive new, itinerant futures. Related GAMING THE SYSTEM CLAIM TO FAME E-Test

Like the lowercasing of his name, garcia’s art possesses a transgressive humility and embraces improvised play and mutability, largely in response to his past and in accordance with the way he exists in the world. The artist grew up moving between Northern Mexico and California, where his parents worked as migrant farmers; he identifies as an individual with an unfixed sensibility. In his words, “If I must identify myself, I am a queer Chicanx world citizen, belonging somewhere else.” In bozales (muzzles), 2015—an assemblage of plastic, steel, and leather dog muzzles—garcia draws on his haunting memories of crossing the border as a child, but as in many of his works, the reconfiguration of materials and references suggests displacement, constraint, and yet a sense of agency. Like his nomadic practice—based for now in New York and central Mexico, but frequently moving from place to place when he is offered employment—the elements garcia uses to create his sculptures can migrate endlessly to become parts of new pieces. He conceives his art to remain unfinished; when a work is acquired, he considers it “on pause.” A sculpture might in one installation be scattered across the floor and in another aggregate through impromptu vignettes with added objects, based on a particular space and the artist’s intuitive “internal matrix.”

Following an improvised set of conditions, garcia constructs environments in which something uncontrolled might develop. These installations are inhabited by materials that behave in ways they aren’t meant to, and objects that accumulate new and multiple meanings. Delicate ceramic links are pieced together to resemble rugged metal chains in works like cadena perpetua II (life imprisonment II), 2018. For matanza (slaughter), 2012, skeins of flayed animal hides are tenderly hand-sewn into a leather wall hanging that evokes an empty body bag and references the Aztec god of both war and agriculture, Xipe Totec. garcia transforms raw goatskin into patchwork rugs like luna llena (full moon), 2016, which recall antiques stores and street markets he visits in Mexico, “‘ranch homes’ as an aesthetic,” and “rustic country whitewashed cowboy paraphernalia.” Meat hooks both threaten and connect (as in más o menos [more or less]), 2016; spools of copper wire are perpetually crocheted into lace. His formal collisions suggest the seemingly contradictory qualities of fragility and strength, of bondage and machismo as expressed through “feminine craft.” He reframes now-ubiquitous decorative objects as symbols of class, the appropriation of vernacular culture, and violence against nature, discreetly relaying a critique of a binary, hierarchical worldview that intersects with his own family history.

Refraining from what artist Aria Dean has aptly called “cannibalizing biography,” garcia evokes the personal by leaving almost imperceptible imprints of a body, often his own, on the work and by incorporating symbolic threads that resist the legibility of narrative. The sense of an unseen hand propels his rigorous labors of sewing, weaving, and welding, all possessed of the vitality of the indigenous traditions that endure in Michoacán and Zacatecas, Mexico, where his family lived for generations. The hand-mottled figurine in mitla, 2018; the crocheted workman’s glove in manos a la obra (let’s do it), 2016: Such works give shape to unseen bodies—often erased from historical narratives—and their obscured subjectivities. In mitla, titled after the important spiritual site in Oaxaca (and also the Zapotec word for “underworld”), the pinched ceramic statuette abstracts human form to mere signifier, while a shimmering glaze of metallic palladium renders it an object of devotion. In manos a la obra, garcia’s meticulous threadwork foregrounds the manual labor that produced the empty glove, its wearer unknown. Such motifs of resolute absence and presence recur, pointing to the invisibility of systems that render individuals as well as entire cultures as such.

Although garcia gleaned many of his material processes from watching members of his family and community perform them, he gained his knowledge of the work of the Zapotec, Aztec, Olmec, Maya, and other indigenous Mesoamerican civilizations through research, exploring his relationship to histories that remain only partially intact, and art that is popularly presented as archaeological remains. Wrestling with how these histories (largely fragmented due to colonization) and the related systemic issues manifest in his private and psychic life, the artist turns to tactility, surface, and structure to register not only the feeling of what is missing or has been undone, but also that of what can be reclaimed. This might seem to imbue his sculptures with a sense of loss, but it reveals too how disappearance—as an artistic strategy—can disrupt; this affect is captured in the title of his 2018 show at Mary Mary in Glasgow, “deshacer, or: to undo.”

Like the lowercasing of his name, garcia’s art possesses a transgressive humility and embraces improvised play and mutability, largely in response to his past and in accordance with the way he exists in the world.

Take desmadre, 2016, the title of which translates as “chaos” or “mess,” and which comprises an array of found and made objects including a round crocheted rug of wool and horsehair; a bespoke copper wheel; pieces of glass; a roughly carved totemic pipe with air punctures suggesting eyes; and various smaller pipes, bracelets, and other items. All are dispersed along the perimeter of the gallery space, calling to mind a street merchant sale or roadside memorial and giving the installation a sense of vulnerability. While works like this one offer oblique connections to garcia’s childhood memories of economic instability, they also summon intimate images of familial love and community: his grandmother making clothes and doilies in her Tabasco home, either to sell or for her children to wear; vendors hawking vessels made of palm, ceramic, and natural fibers, crafted using techniques that have been passed down through generations. garcia reasserts these modes of making as noble and valid forms of nonhierarchical production and economic exchange.

In another body of work, “portales” (portals), which he began making in 2017, the artist faithfully re-creates centuries-old stitch patterns—frequently used in Mexico, if not entirely indigenous to it—to build a series of woven-fiber and copper screens that conjure other temporal registers. These thresholds form a permeable architecture, occasionally adorned with relics of control and pain that double as ancestral apparitions: a metal spur found on the small Zacatecas ranch where his family lived; a self-flagellation rope, studded with small nails, of a kind frequently sold outside Catholic churches in rural Mexico. garcia’s allusions to pain are sometimes read alongside his use of leather and latex as formal nods to s/m sexual practices. “I often use materials which reference violence, sensuality, and the body,” he explains. “Intriguingly, white art audiences and viewers have often mistakenly taken the presence of these signifiers as literal, or to reflect a certain ‘kinky’ sensibility.” While noting the importance of sexual subcultures in society at large, garcia is more interested in addressing how inversions of power can devolve into pastiche or fashion. In his sculpture yes, yes, yes, thank you, thank you, thank you, 2018, chains coil into holes for arms and a head, echoing a stylized replica of colonial American stockades that garcia once saw at the Laird, a gay bar in Melbourne.

His use of organic latex in works such as figura (figure), 2019, pays homage to the sculptures of Eva Hesse and Louise Bourgeois in their associations with the natural world and particularly as visceral indexes of grief. “The subject of pain is the business I am in,” Bourgeois wrote in 1991 in the catalogue for the Carnegie International in which she debuted “Cells,” a series of architectural installations she produced until 2010. “When does the emotional become physical? When does the physical become emotional: It’s a circle going around and around.” garcia’s work offers a similarly complex psychological landscape, reflecting a belief that one’s inner life is not an imaginary realm, something apart from the rest of the world, but is a kind of material. He views weaving as a meditative practice that allows him to process emotional injuries that are intimately entangled with broader power dynamics. “Emotionality is political,” says garcia, based on the fact that some are granted the right to live and love as they want, to know and understand their own history, and others aren’t. In corpus, 2018, eroded half orbs of glazed ceramic and vegetable fiber are varyingly stitched together with fine copper wire, with needles haphazardly abandoned mid-stitch and holes gaping around the filament; these details of the work bring to mind the sutured peels of Zoe Leonard’s Strange Fruit, 1992–97, and the notorious image of David Wojnarowicz’s lips sewn shut, as well as his Untitled (Bread Sculpture), 1988–89, for which he reconnected two halves of a loaf of bread with loose red thread. How does one repair what is broken, what has been taken, what is now gone? Although garcia’s work does not address the hiv/aids crisis of the ’80s and ’90s, or what it means to grieve and move forward during an epidemic, there is a crucial kinship in his understanding that life is fragile and must be protected, must find resilience, by being given dignity and care.

He conceives his art to remain unfinished; when a work is acquired, he considers it “on pause.”

In la mano del Xipe Totec (the hand of Xipe Totec), 2016, garcia again cites the deity of death and rebirth, as well as of liberation, disease, and spring, often depicted in codices with his right arm raised and wearing a flayed human skin. garcia’s sculpture presents a large ceramic arm extended upward; its hand has been given a bronze-like patina but is glazed from the wrist down in white as if wrapped in a second skin. It sits atop a shoeshine stool, an antique purchased from a vendor at the Lagunilla market in Mexico City, which points to the often unseen and underappreciated labor performed on the streets. A scrap of leather in the shape of an arm rests at the stool’s feet—a reference to the ersatz skin of a sacrificial victim that was worn as a costume by participants in ceremonies held to honor the deity and bring a good harvest. If not directly spiritual or linked to mysticism, garcia’s practice, throughout all of his work, engages in the forms of ritual to render visible the largely forgotten or undervalued belief systems and stores of knowledge that have impressed themselves upon him regardless, both viscerally and intellectually. With his invocation of mythologies, garcia reminds us of the impossibility of fully understanding our paradoxical universe—one that is at once menacing and nurturing—and of the imperative to locate ourselves in it nonetheless.

Margaret Kross is a curatorial assistant at the Whitney Museum of American Art.

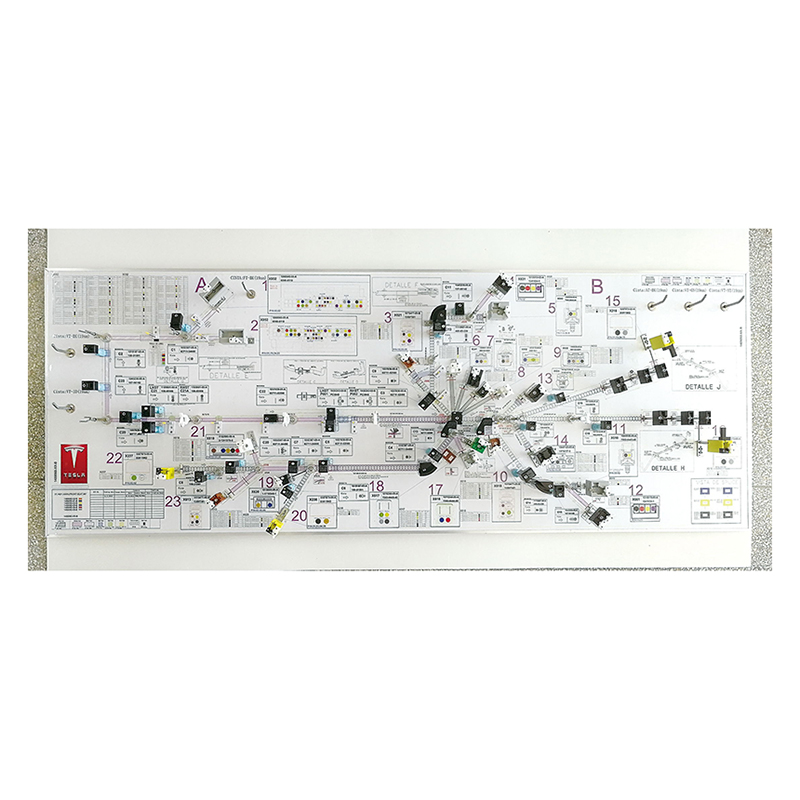

Electrical Panel Wiring By providing your information, you agree to our Terms of Use and our Privacy Policy. We use vendors that may also process your information to help provide our services.